Local History Topics

Logging on the Kickapoo

By Brad Steinmetz - Part I

Men rode the rafts and guided the logs away from sandbars, and through dams and eddies in the very dangerous work of driving the logs down the river. This group of rafters includes Gus Smith (back row, far right), Billy Gibson (standing next to him), Louis Kinnear (front row, second from right), and Harv Collins (front row, far right). Image donated by Dave & Donna Heilman of Ontario.

Monday, September 14, 2020, marked the 150th anniversary of a tragic accident that took the lives of three young men. That tragedy also serves as a major marking post for the early history of not only La Farge, but the entire Kickapoo Valley. A poem that was written about the accident went on to become a key part of the folk history of lumbering in America. That poem, written by Abagail Payne, was titled “The Fatal Oak”.

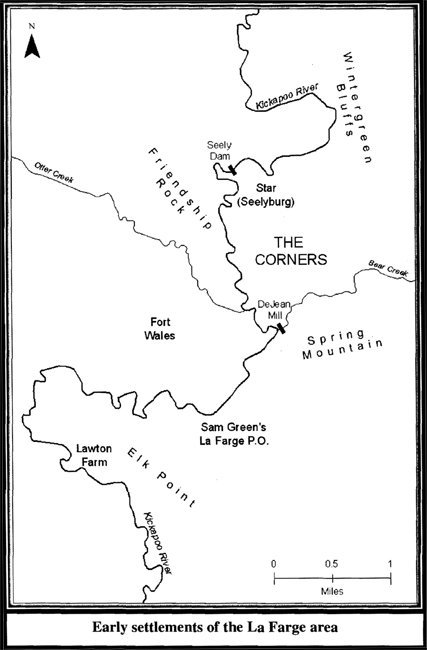

It was a time of earliest migration as land was purchased from the federal and state governments and people first made homes in this beautiful valley. It was a profound time of change as forests of pine from the Kickapoo Valley helped build the foundations for western expansion in this country. Lumber mill owners like Giles White, Van Bennett, Dempster Seeley, and Thomas DeJean owned thousands of acres of this valley and the surrounding hills. They ran lumbering businesses that employed hundreds of people and entire towns grew around those operations.

The Kickapoo River was the avenue of success during those times. The river was used to float the logs to the mill sites; the mills were run on the river’s power; and the finished pine lumber was floated on the river to markets where the lumber was sold. By the 1890’s, the river rebelled over the use and abuse of lumbering and the floods began. As the Village of La Farge was being created, the town of Seelyburg was starting to be washed away by the floods of the Kickapoo. But the river’s floods could not wash away that heady time of the lumber boom that started in the 1860’s and stretched for over thirty years towards the present.

Interestingly enough, that early boom time of lumbering on the Kickapoo is well documented. That may be because that time came first in the settlement of the valley, so people noted those significant milestones. It may have developed from a romantic idealism about those pioneers developing the lumbering industry. Yet, that time may be remembered best because of a poem written about a log rafting accident that occurred in 1870 that took the lives of three young men of Seelyburg. The poem, written by Mrs. Abigail J. Payne, was “The Fatal Oak”. That poem, which is really a eulogy to those three lost boys, may give us a better glimpse into that time than any other source that we could find. Melodramatic and maudlin it may be, but Abigail Payne’s poem has stood the test of time and still remains today a fascinating glimpse into life on the wild Kickapoo. It was certainly a different time.

By 1870, Dempster Seely’s mill operation in the village of Star was a thriving business. Much of that business involved sawing up rough lumber and then rafting it down the river to be sold. That lumber was used to build Galena, Illinois; Dubuque, Iowa; and other Midwestern cities. Railroad ties made from Kickapoo Valley lumber were used to lay the transcontinental lines stretching out to the western frontier. Lumber mills in the Kickapoo Valley like Seely’s would build rafts of the cut lumber and crews would guide them down the river. The lumber would first be assembled into what was called a crib, usually eight to twelve feet wide and twelve to sixteen feet long. The crib would be bound together by logs or rough cuts around the edges so that it wouldn’t come apart in transit. Several cribs, anywhere from eight to twelve in number, would be tied together to form rafts, some over 100 feet in length. A great wooden tiller would be placed on the front of the raft to steer it in transit and long wooden gaffe poles would be used to guide the rafts around obstructions in the river. A short rudder in the rear of the raft would help in steering. At least two raftsmen were needed for each raft as it traveled the river.

The original Seely dam.

In September of 1870, Seely’s mill had two rafts ready to be floated down the river, with Anson DeJean being Captain of the venture. DeJean was the adopted son of Thomas DeJean and together, they had built the first lumber mill on the river in this area back in the late 1850’s. That mill was at the mouth of Bear Creek, but didn’t function well due to a lack of water fall at the site. (The mill was later converted to a gristmill, which continued to operate into the 20th century.) Seely’s mill, two miles to the north, soon eclipsed DeJean’s operation and Anson went to work there. Anson DeJean needed a crew of four to aid him in his rafting trip. Wash Wilson, George Lawton, James Roberts, Aaron Hatfield, and Bert Wood, all “Seely men”, were available for the trip – one too many. To eliminate one, Hatfield and Wood drew wooden cuts, with the longer draw making the trip. Wood drew the shorter cut and as he would say later,” To a small piece of wood, held in the palm of a man’s hand, I probably owe my life”.

Marietta Seely, wife of the mill owner, would have baked bread and sweet cakes for the rafting crew’s trip. Food would be stored in a “grub-box” built on one of the cribs, kept there to stay dry. The men slept on blankets stuffed with straw during the voyage. The trip to the mouth of the Kickapoo below Steuben usually took three or four days, longer if water levels were low. Often, one of the boys would run ahead to the next town or mill site on the river, so that the dam could be opened to let the rafts through. Guiding the rafts through the dams was tricky business and took the most skill to avoid breaking up the raft or soaking the food in the grub-box. Once out on the Wisconsin River, the rafts were taken down river to a site where they joined other rafts for the “through trip” on to the Mississippi River and its market towns. Near this site, the fateful crew anchored at a favorite spot by a large oak tree, its roots washed bare by the current, and stayed for the night.

The next morning DeJean headed to shore to start breakfast. On shore he noticed the oak tree starting to lurch and fall towards the rafts where the crew of four were still sleeping. He yelled a warning, but only Wilson heard and jumped off the rafts as the tree came crashing down. The weight of the tree submerged the rafts and the other three sleeping boys were drowned. The bodies of Aaron Hatfield and George Lawton were found after a few hours of searching, but James Roberts’ body wasn’t located. As Anson DeJean and Wash Wilson brought the two bodies back up the river, word soon spread about the tragedy and the people of the river lamented the loss of their brethren. Hatfield and Lawton were brought back to Seelyburg and buried with their kin. Roberts’ body was eventually found near Wyalusing and buried there along the river. Soon his family and friends went to the site and brought the body back home for burial in Star Cemetery in Seelyburg.

Abigail Payne, wife of Truman, lived in Wauzeka at the time of the accident. She was a good friend of the DeJean family and came north up the river to comfort her friends after the tragedy. Her poem, “The Fatal Oak”, was written for the DeJean family. Later it was published in the Viroqua newspaper, submitted by Anson DeJean. The poem became very popular and was always read at public gatherings in the area for decades after the accident. A variety of versions of the poem evolved over the years, and the poem also came to be a folk song, sung in the form of an elegy or dirge. Eventually the folk song was recognized as an important chronicle of local history and was recorded and added to the list of prominent folk songs in the state of Wisconsin. The last verse of Abigail Payne’s poem reads:

We leave them in the silent tomb

While many friends are left to mourn

With kindred friends whose hearts were broke

By the sudden fall of the fatal oak

MENU

MENU