Local History Topics

Logging on the Kickapoo and "The Fatal Oak"

Contents:

The River

The Kickapoo River is sometimes referred to as the “crookedest river in the world.” The river measures 126 miles long, but only travels 60 miles from start (near Wilton in Monroe County) to finish (at Wauzeka in Crawford County) where it drains into the Wisconsin River. For the Wisconsin River, it is the largest tributary in terms of drainage (800 sq. miles), and second only to the Tomahawk in terms of water flowage. The name Kickapoo comes from the Algonquin word kiwegapawa meaning "he stands about" or "he moves about." Aptly named for both the meandering river and the Kickapoo people who moved in and out of this area in the 1600s.

When one thinks of logging in Wisconsin, it is usually the north woods that come to mind with its great stands of pine woods and logging camps. The Kickapoo drainage, however, had a substantial pinery of its own. The reason for this is that the topography of the Kickapoo Valley creates what is known as a fire shadow. Whether naturally occurring or set by Native peoples, fire kept the driftless uplands in prairie grasses with small, isolated stands of hardwood forest. For the most part, the winds pushing the fires came from the west, so often eastern slopes, especially those near water, were protected from the blaze creating a fire shadow. This promoted thick forest growth of hardwoods – white, red and burr oak, elm, sugar maple and hickory; with a dense undergrowth of prickly ash, ironwood, hazelnut and green briar; plus an abundance of pine.

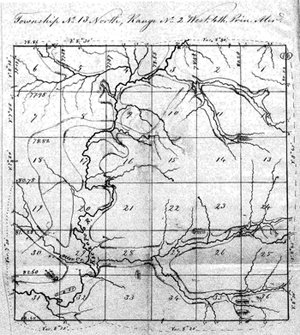

The Kickapoo drainage in Vernon and Richland Counties.

The Land

Early descriptions of the area emphasize the heavily forested Kickapoo Valley. In 1832, militia who were chasing after Black Hawk crossed the Kickapoo at Pine Grove (Soldiers Grove today) and recorded how thick and difficult it was trying to get through the woods, and that there was nothing there to feed the horses. In an ironic twist, when they finally emerged on the plateau above, there was ample forage for the horses but no wood with which to build a fire.

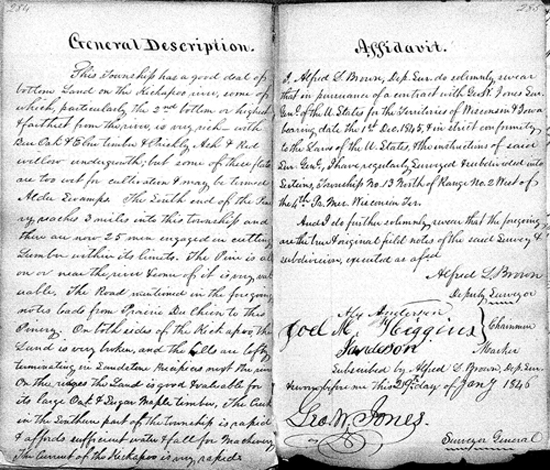

Surveys conducted by the federal General Land Office (GLO) in the 1840s include descriptions of the townships along the Kickapoo River. They generally describe the Kickapoo Valley as heavily wooded with various types of oak and pine, and not good for agricultural purposes. Even at this early date, prior to official European-American occupation of the land, men were already busy cutting down pine. From the 1845 GLO of Stark Township: “The South end of the Pinery reaches 3 miles into this township and there are now 25 men engaged in cutting Lumber within its limits. The Pine is all on or near the river. Some of it is very valuable.”

Stark Township GLO description and map:

The Logging

Having valuable pine and hardwood is a great asset, but how did people make use of the lumber and get their product to market? There were very few roads, no railroad in the region, and hauling logs or lumber via horse-drawn wagon was a long and ineffective process. Later, northern loggers would make use of the major waterways leading to the Mississippi River, but how to float rafts of lumber down the meandering, relatively shallow Kickapoo? From the GLOs, we learn that the Kickapoo had a larger volume of water in earlier times, and a much faster flow. The same GLO of Stark Township mentions that “The current of the Kickapoo is very rapid.” The Liberty Township GLO of 1840 states “The streams have a quick and sometimes a rapid current, with clean shores and a gravelly or stony bottom. Numerous springs of pure water gush from the hills and heads of ravines.”

By the 1850s, European settlers were living and building along the Kickapoo River. Some of the first settlers were lumbermen from the east such as Thomas DeJean and Dempster Seely, and they immediately built sawmills and dams on the Kickapoo and its tributaries to take advantage of the river and valuable lumber. They provided the lumber for local structures as well as sending lumber downstream to the markets in Iowa and Illinois. They also provided most of the ties used to bring the railroad to this area in the 1890s. Lumber was rafted down the Kickapoo to the Wisconsin and on to the Mississippi. We learn from Brad Steinmetz’s book La Farge: The Story of a Kickapoo River Town that dams provided more than waterpower to the mills. As the raft was coming down the Kickapoo, men would run ahead to tell the dam operators to close the dam creating a swell of water. When the raft got close enough, they would open the dam allowing the water and the raft to shoot downstream.

Ralph Eswein of Black River Falls, author of the 1995 book, Logging Dilemma in the Big Swamp, gives the following explanation of this photo:

“In very early logging, the rafts were the best way to get the sawed lumber to the markets, like St. Louis. First a number of cribs (10 or so) were made of large timbers (maybe 8’x8’) and they were pegged together. In your photo notice all the pegs sticking up thru flat boards around the edges of the rafts. These were made of oak or other very strong wood, usually cut from the woods as pegs. The cribs were then filled with rough sawn lumber laid crosswise. Some stringers were laid lengthwise and pegged in place. Since the rafts would go thru many rapids on their way to calmer waters, they had to be flexible from end to end.

“The long central poles on your rafts were for steering, one in front and one in the back. Notice they were pegged on the board across the front, a focal point for steering. There were usually one or more doghouse-type small enclosures built in the middle of the raft for food and dry clothes, etc. Your rafts are rather small, but so is the Kickapoo River, so makes sense. Three men would usually man the raft. Most had a spare man in case someone fell overboard and drowned.”

MENU

MENU